Mildew hit amateur growers hard last year. But what exactly is mildew? How can you recognise it? How serious is it? What can you do to prevent it happening? And how can you get rid of it?

First, what is mildew?

Mildew is a fungus that looks like a dusting of castor sugar on the leaf and that harms the plant. There are many types of mildew. Very often a particular type of plant will have its own mildew, and that's because diseases often evolve in line with the host plant. One type of mildew will attack cabbages and another only cucumber plants. Mildew can turn out to be so specific that it selects a specific variety. A form of mildew that attacks grains may prefer, say, either rye or wheat as its host, but not both.

Mildew variants have been given elegant Latin names such as Sphaerotheca macularis and Leveillula taurica. The first one has a taste for hops and strawberries. Blackberries and violets can also act as their host, meaning that this fungus remains fairly specific compared with other types of mildew. This mildew is far from choosy when it comes to its choice of host, infecting thousands of plant types, including many vegetables.

Recognising mildew

Before any symptoms become clear the leaf starts to develop blister-like patches, and this is followed by the characteristic white powder where the blister was. The leaf looks as if it's been dusted with powder. In general mildew is found on the upper side of the leaf, but there are exceptions. One type of mildew only grows on the underside of the leaf, so it's no surprise it often gets overlooked.

True or false mildew?

False mildew looks like true mildew. The general rule is that false mildew is found on the underside of the leaf, with true mildew on the upper side of the leaf. But that's the general rule: as we noted just above, true mildew can sometimes be on the underside of a leaf.

P. humuli or Pseudoperonospora cannabina is one such false mildew. Taxonomically this is rated as identical to another false mildew, P.cubensis, that causes problems in cucumber cultivation. It first appears on the underside of the leaf in the shape of brown or even black discolorations that then turn into a fungal web that's a sort of violet going on grey colour. A mosaic of dying patches starts appearing on the upper side of the leaf. This mildew is known for attacking hop cones and causing them to turn brown.

Types of mildew

If you find mildew in your plants, this table will help you make a stab at the type.

| Fungus | Colour | Leaf side | Patches | Rub it off? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphaerptheca macularis | White | Upper side | No | Yes |

| Leveillula Taurica | White | Under side | No | No* |

| Pseudoperonospora Cannabina | Grey | Under side | No* |

* Patches stay on leaf

1. Sphaerotheca macularis

This true mildew grows on the upper side of the leaf (figures 1 and 2). Its optimal spore reproductive conditions are temperatures between 15 and 27 degrees and relative humidity in the 75% - 98% range. But when relative humidity is lower the fungus happily compensates for the reduction in the number of successfully germinating spores by increasing the numbers released. So relative humidity is less of a factor for survival of this fungus. Rain and persistent dew do, however, hamper its dissemination.

2. Leveillula taurica

The fungus can survive on a great many other plants and on dead plant material such as leaves. It is fairly insensitive to climate. It is comfortable in temperatures between 15 and 33 degrees and is equally at home in conditions of low and high relative humidity, with between 75% and 85% being its favoured range. Infections often start in the older leaves of mature plants. In addition to direct damage, infection caused by this mildew will render the tops more sensitive to being scorched in the sun.

3. Pseudoperonospora cannabina

Pseudoperonospora cannabina is a false mildew that grows on the underside of a leaf. Unlike a true mildew the colour of this fungal web is not so much white as grey. The fungus usually gets discovered because yellow, later brownish, patches start appearing between the veins on the upper side of the leaf (figure 3). Ideal conditions for this fungus are temperatures between 15 and 22 degrees and relative humidity between 80 and 100%. Pseudoperonospora cannabina can also survive in seeds from infected plants in the ground.

Infection

If the conditions on the leaf are ideal (let’s say the right temperature and humidity), a spore landing on it can germinate. A fungus filament will pass from the spore via a damaged part of the leaf or a stoma into the interior, and here the circumstances must be favourable as well. The filament then thickens and once it has penetrated properly a secondary thickening process takes place, and this allows the fungus to absorb nourishment from the plant cells. Further thickening then follows with more filaments (in the case of L. taurica this will be mainly on the plant the first time and in the case of S. macularis it’ll be on the surface of the leaf). The fungus then forms reproductive organs from which, by asexual reproduction, new spores are expelled into the air, so beginning the infection cycle.

Conventional types of mildew such as S. macularis only grow on the leaf surface, not inside the leaf. As we have seen, L. taurica is no conventional mildew. It can grow for 21 days hidden away inside the leaf tissue before coming up at the surface. This means that once an infection can be spotted, many more leaves have been invisibly infected.

True mildew spores need to be able to germinate and then to be able to grow into the leaf. Germination calls for the spores to have moisture on the leaf such as dew. But sprouting requires a dry leaf.

The chances of infection are therefore the most acute during a dry, warm period when there's condensation on the plant in the mornings, which happens when the air warms up faster than the plant itself. If the plant is suffering from dehydration, then it's extra sensitive to such an infection.

Plants in tunnel greenhouses or in poorly ventilated areas are especially susceptible to mildew infection, especially if moisture on the leaf evaporates within three hours as the heat rises or with a bit of a draught. These are ideal circumstances for spores to germinate and sprout. Draughts are also excellent for spreading spores.

Products against mildew

Until now, only chemical products have proven their effectiveness against a mildew infection. One example of the relatively effective products you can buy at your local garden centre is that of triasol-based compounds (triadimenol, tebuconazole and bitertanol). If your plants have more or less completely stopped growing, as in the last weeks before the harvest or in the case of a very severe mildew infection then these systemic products will not work well, and you will need a direct contact product. Unfortunately these aren’t known for their effectiveness. The reason is that mildew needs to be attacked directly and every patch that gets omitted will remain.

Compounds based on chlorothalonil, imazalil or myclobutanil are contact products for use against mildew. This group of compounds has recently been supplemented by a naturally derived product that attacks true mildew with the help of enzymes. CannaResearch is carrying out extensive research on this, together with other naturally based compounds. CannaResearch advises against the use of sulphur spraying as a contact product because this leaves residues that are visible for a very long time.

And the damage?

The share of harvest you may lose is very much a question of whether the infection has been limited to the leaf, but if the infection has attacked the fruit as well losses can be as high as 100%. The period when the infection hits is also significant. If the infection comes late in the cultivation it’ll have significantly less of an effect on the yield than one that hits when the plants are still young.

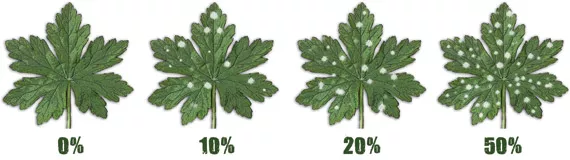

The rule of thumb is that mildew growth accounting for 1% of the leaf surface equates to a 1% reduction in harvest. A surface that has been attacked tends to get overestimated, and drawings have been prepared to help in making the estimates (figure 4).

In conclusion

Climate control is the key to avoiding mildew infection. Good ventilation and not too high a level of humidity are indispensable, as is ensuring that moisture on the leaf gets followed by dry conditions. In general harvest losses resulting from a mildew infection will not be too heavy, but if the plant gets infected early on in its life cycle or if the tops get infected the damage can become pretty serious.

The point here is that, even if you use chemical products, it’s difficult to do much against an infection towards the end of the cultivation or against a severe outbreak. Climate control is one thing, but checking frequently for mildew and reacting on time are important too. It may be impossible to guarantee you’ll never have any mildew problems, but we’d like to hope that this article will help you reduce your chances of major problems.